EBERTFEST 2025 brought stories of empathy to its audience

CHAMPAIGN-URBANA, ILLINOIS—Walking into the historic Virginia Theatre, Ebertfest patrons were greeted with the sounds of organist Dr. Stephen Ball playing songs both historic (“My Favorite Things”) and contemporary (“Defying Gravity” from Wicked). It’s a wonderful way to set the mood in preparation for what was a thrilling and challenging few days of screenings in this college town that is home to the University of Illinois—and my former home in 2013 to 2014.

“Ebertfest is alive with the sound of music,” Chaz Ebert, Roger’s widow, said Thursday morning as Ball took a bow.

Chaz thanked the enthusiastic crowd, and made sure to briefly mention her new book: “It’s Time to Give a FECK: Elevating Humanity Through Forgiveness, Empathy, Compassion and Kindness” before getting down to the business at hand: Keeping Roger Ebert’s film festival going even 12 years after the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic’s death.

“Roger really did think that movies were a machine that generates empathy and [respect for] people who are different from us…and make the world a better place,” Chaz said from the dais at the Virginia, adding that she and festival director Nate Kohn purposefully choise films this year in that vein. “Some of the films we’ve chosen, you can see…that.”

Chaz introduced “A Little Prayer” writer-director Angus MacLachlan, who also wrote the Oscar-nominated “Junebug,” which Roger Ebert awarded four stars in 2005, and which earned Amy Adams her first Oscar nod.

“I wish [Roger] would have been able to see ‘A Little Prayer,’” Chaz said to MacLachlan, tearing up for the first of several times that day. “You know how much he loved ‘Junebug.’ This one he would love just as much.”

“I think you guys are lucky to have Ebertfest as a lot of independent films…never get the chance to be seen except at festivals like this,” MacLachlan said, adding that “A Little Prayer,” despite gaining positive attention on the festival circuit, has yet to be picked up for distribution.

The film follows a Vietnam-era veteran named Bill (David Strathairn) who runs a small company in North Carolina that employs his son, David (Will Pullen), a veteran of the Afghanistan conflict. David and his wife Tammy (Jane Levy) live with Bill and his wife Venida (an electric Celia Weston), and thus secrets are hard to hide. Bill not only believes that David is suffering from untreated PTSD from his time in the service, but also that David is having an affair with fellow employee Narcedalia (Dascha Polanco). The always-dependable Anna Camp, a South Carolina native, shows up as Tammy’s voluble and perpetually chaotic sister, Patty.

The film, shot in 19 days at the heights of covid restrictions, offers no easy answers, including not revealing the identify of a mysterious singing woman in the neighborhood whose voice is heard most mornings—until one day it isn’t. As the film progresses, the relationship between Bill and his daughter-in-law Tammy comes more front and center, demonstrating a maturity and respect that is absent in their other day-to-day relationships.

“This film is such a celebration of the human condition that Roger championed,” said Kohn—also a film professor at the University of Georgia—at a post-screening Q&A. “I’ve lived in the South now for 25 years, and you got it exactly right.”

Chaz and Cohn were also joined at the post-screening panel by film producer Brandon Ferry and RogerEbert.com managing editor Brian Tallerico.

MacLachlan grew up in Winston-Salem, where he shot “A Little Prayer,” and lives there still. He said that the media often shows Southerners derisively, and he wanted to portray the people he knows so well in a more realistic light. The idea of the unseen singer came from MacLachlan’s frequent trips to New York, when he heard someone singing outside his window at dawn but whose face he could never see.

“She’s bothersome to everyone in the film, but to Tammy and Bill, [the music] is grace,” MacLachlan said.

MacLachan is himself an actor, and because he came from the theater, he enjoyed an artistic shorthand with his cast, including Strathairn, whom he praised vociferously for knowing “how to emote on screen in a way no one else does.” (Chaz said Strathairn was interested in attending the screening, though his schedule ultimately dictated otherwise.)

“I really love actors, and I think these guys are the greatest,” MacLachan said, adding that Strathairn and Weston, on their own, came up with a subtle way of touching one another in character. “I never write with the hubris of writing for an actor because…how could I get them?” He also shared that the performances between Strathairn and Weston were so strong that it led to some ambiguity in terms of a crucial conversation between them, with MacLachan saying he’s a fan of not over-exlaining in his writing and allowing the actors to find the humanity.

In an eerie coincidence, a crucial abortion consultation scene was shot the day the Supreme Court Dobbs decision was announced. MacLachlan shared, with the consent of the actresses, that both Levy and the actress portraying the nurse in the scene had had abortions in their real lives. Just as with reproductive rights, MacLachlan said that the AIDS crisis of the 1980s made D.C. politicians sit up and take notice when it hit too close to home.

“It’s such a different thing when these issues are being argued on the floor of the Senate [versus] when it affects their family,” he said.

MacLachlan worked on the screenplay for the better part of a decade, commencing when his daughter was a teenager and he wished to explore the notion of how fathers, even of adult children, still try to guide them.

Ramin Bahrani, a frequent Ebertfest guest, was a producer on “A Little Prayer.” Chaz recalled how Bahrani visited Roger in the hospital shortly before his death in 2013, and their interaction made its way into Steve James’s documentary “Life Itself,” which took its title from Ebert’s autobiography.

Summing up his journey with “A Little Prayer,” the affable MacLachlan said that he unfortunately has very little faith in the independent film market at present, but he continues to try.

“That’s why film festivals are so important, as you may never get the chance to see it any other place,” he said.

Friday afternoon’s film, “I’m Still Here,” won the Best International Film Oscar in February. Richard Roeper, Roger Ebert’s post-Gene Siskel co-host of “At the Movies,” said Siskel and Ebert would make their own “if we picked” list of winners. Roeper shared that “I’m Still Here” was his personal pick for best film of 2024, calling it a testament to the power of family and of the importance of a strong matriarch.

The film dramatizes the real-life story of Eunice Paiva (Fernanda Torres), a Brazilian wife whose politician husband Rubens was disappeared during the country’s brutal dictatorship of the 1970s and ‘80s. Eunice and one of her daughters were tortured, and the authorities continued to stonewall any attempts to find Rubens. Eunice’s very public quest for answers continued for the rest of her life, outlasting the dictatorship. The film’s single most frightening scene involves men from the Brazilian army simply closing the house curtains inside the Paiva home.

(In a casting coup, the elder Eunice is played by Fernando Torres’s own mother, Fernanda Montenegro, a legend in Brazil’s acting community who is now 95 and still working.)

Choking up a second time, Chaz Ebert said that following the November election, she took an “official day of mourning.” She was gobsmacked that American voters had once again chosen to support a regime Chaz, an attorney by trade, views as “tyrannical.” “It hurts every day to see people snatched off the streets,” she said. “Sometimes I’m afraid to be in this country.” However, she turned that agitation into pride with a spontaneous rendition of the song “I like the United States of America.”

In the interests of speaking truth to power, she chose a post-screening panel to focus on issues of press freedom. Joining Chaz and Roeper were Brenda Butler of the Chicago Tribune and Matt Zoller Seitz, editor at large at RogerEbert.com.

Zoller Seitz described “I’m Still Here” as a “knockout,” not only for portraying the horrors of living under totalitarianism but also how mundane can be the process of continuing such day-to-day activities as taking the children to school. Butler agreed, saying that it’s rare for a film to focus on a single mother such as Eunice Paiva. The panel also played the “what if” game, had they been alive in Germany in 1939.

“Whatever you would have done is whatever you’re doing right now,” Zoller Seitz said. “People are watching what they say [in journalism], and even during the Iraq War, it wasn’t like this.”

“[Paiva’s attitude was] we’re not going to show that we’ve been defeated by these monsters; we’re going to smile and go on,” added Roeper of a famous photo—recreated in the film—of Paiva and the children smiling broadly despite their missing paterfamilias. “She’s never in denial mode; she’s in survival mode for her children.”

Brazil’s current far right tried to quash “I’m Still Here,” offering a familiar refrain of “it’s time to move on.” However, such attempts at proscription only heightened interest in the film, which became a hit in Brazil. Eunice Paiva’s children are now journalists, lawyers and filmmakers.

Chaz said the film also speaks to the idea of generational trauma, which she relates to as the descendant of enslaved African Americans. Some firms in her field of law have stood up to the current administration, however, many others have caved to the pressures.

“We were always taught you don’t give in, you don’t give up. You fight,” she said, pointing to such stances as that of Harvard and Champaign-Urbana’s own University of Illinois refusing to bow to the White House’s demands to amend or end their on-campus diversity efforts. The panel also decried the current digital media oligopoly bending the knee to the will of Mar-a-Lago. Zoller Seitz said media owners have come a long way since Katherine Graham and Ben Bradlee at The Washington Post chose to potentially alienate many of their D.C. circle by publishing the Pentagon Papers. (Disclaimer: I work part-time as a copy editor on the Post’s opinion desk.)

There’s a small moment in the film where one of Eunice’s jailers tells her, “I don’t approve of this.” Chaz related an anecdote about how Desmond Tutu absolved his own jailers and became friends with a particularly kind guard. “You have to forgive; otherwise, you will just remain a prisoner,” Chaz paraphrased Tutu.

On Friday evening, before introducing another film, Chaz stepped away from the dais and her microphone to, as she said, get a feel for the vibe of the audience inside the Virginia.

“With so much going on in the world, I look for good wherever I can find it. And here I find it,” she said, praising Ebertfest staff, including Kohn, assistant festival director Molly Cornyn, and the army of volunteers it takes for such an event.

“I think about it at the beginning of the film festival, and Roger telling me that he felt like a little boy who had gotten a train set for Christmas,” she said of what began as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” “We were only supposed to do it for one year, but anything you do with Roger for one year, he calls a tradition. I honestly didn’t think that twelve years after his leaving this earth, that we would still be meeting here in the Virginia Theater.”

Cohn then introduced “Rumours” from Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin. With an impish grin, he invited the audience to “empty your mind and let the film wash over you and see what sticks.”

The black comedy centers on a meeting of the G7 leaders. Soon after being left alone to draft a statement, they discover their staff, their advisers, and seemingly everyone else has vanished without a trace. Strange creatures are roaming the woods. The powerhouse cast includes Cate Blanchett, Denis Ménochet (“Inglorious Basterds”) and the English actor Charles Dance as the American president—which Maddin “explained” in the post-screening Q&A, in which he Zoomed in from his home in Winnipeg.

“I was thinking, what’s the new way of filling that roll and [cowriter] Evan Johnson said ‘The American president is British,’” Maddin said, adding that he and his cowriters Evan and Galen Johnson purposely left this mystery unanswered—offering, as if in explanation, “What if they became a colony again?” (He said Dance has been “tortured” by the question at multiple screenings.)

Maddin had been scheduled to come to Illinois but was advised by his team not to in the current political climate. He made light of the current frosty relations between Ottawa and Washington: “I couldn’t afford the burner phone and burner laptop that was recommended. Also, I couldn’t afford to be detained.” During the Q&A, a lady in the balcony told Maddin she had driven over nine hours from Milton, Ontario, to hopefully meet him in person—also deleting her social media before crossing the border “just in case.”

The idea for what became “Rumours” went through several iterations, but Maddin said he and his writing partners kept coming back to the idea of supernatural “bog people” as a great story element. Watching G7 moments, he said, fascinated the team, which he said reminded them of a “geopolitical silent movie” wherein the world’s most powerful leaders were essentially performing for the cameras.

Chaz asked if the film’s fictional Canadian prime minister, played by Roy Dupuis, was inspired by Justin Trudeau. Maddin responded that the character, Maxim, is “kind of what Justin Trudeau thinks he is.”

When the script found its way to Blanchett’s camp, the Australian multiple-Oscar-winning actress arranged to meet Maddin for a video chat. Their discussion lasted for 61 minutes, he said, and only the final minute centered on the business at hand as she agreed to come aboard.

With such a smart move to his credit, it might be somewhat surprising to hear Maddin say that he and the Johnsons are such fans of “being dumb” in movies. In addition to the bog people, the other thrills of “Rumours” include a giant brain whose presence in the woods is never fully explained.

“I’d always wanted to put a giant brain in something,” Maddin shrugged. “I wasn’t even sure if this was a comedy or if it was funny enough to be considered a comedy. There’s always something wonderful even in a bad movie. Luckily enough, critics have loved this that I can ignore the ones that don’t.”

An Ebertfest tradition is the annual silent movie screening with live music. This year’s entry, “The Adventures of Prince Ahmed,” from 1926, is a German film directed by Lotte Reiniger. The film is a stop-motion animation surreal adventure involving the prince, a flying horse, several strange demons, and side trips to China as well as the Middle East. Terry Donahue of the Anvil Orchestra led the pit ensemble of two musicians in recreating the experience of what audiences a century ago might have experienced while watching the silent film during the medium’s infancy.

Donahue said he first met Roger Ebert at the Telluride Film Festival, which led to his eventual relationships with the festival. Donahue, a veteran of Boston’s rock music scene, jested that he has spent quite a lot of time in the food service industry to pay the bills before essentially becoming the leader of a small traveling ensemble to create live music for silent films.

“The hardest part is coming up with the very first piece of music, and then scene by scene we score it and hopefully [string it] into one solid performance,” Donahue said. “Some [films] lend more to the improvisational side, and some are more structured.”

Even if there was an “original” score for a silent film, he said he would much rather rely on his own artistic interpretation. This enables him to utilize instruments that weren’t even in existence 100 years ago, including the synthesizer. “If you just play music from the ‘20s that’s pulling you back instead of moving you forward,” he said, adding it used to take upwards of two months to come up with a score; now the themes come much quicker, allowing for room for improvisation and creativity during the performance.

If he does his job properly, Donahue said, the audience will forget he and his collaborators are there in the pit. Another compliment he gets often is “next time I’ll watch the movie” instead of the musicians.

The panel was moderated by Omer Mozzafar, lecturer in Islamic studies at Loyola University Chicago. Because “Prince Ahmed” features what to our eyes might look like regressive stereotypes, an audience member asked Mozzafar if he was bothered, especially by the Middle Eastern characters in the film. He responded that the film came out during an “era of Orientalism” where depictions of non-Western cultures were often presented in terms of either pageantry or savagery.

“I’m looking [first at] is it entertaining, and then looking beneath the surface,” he said, adding that when he took his own daughters to Disneyland, but they weren’t able to locate Princess Jasmine, his tart response was: “Maybe she’s been held up by TSA.”

“You don’t want to erase history; that’s what they were showing then,” added Donahue. “So you show it and then you have the conversation. You don’t want to shy away from it.

“People [ask] ‘Aren’t you exhausted afterwards?’, and I say much more emotionally than physically exhausted because of…throwing yourself into the film and into the music,” he said.

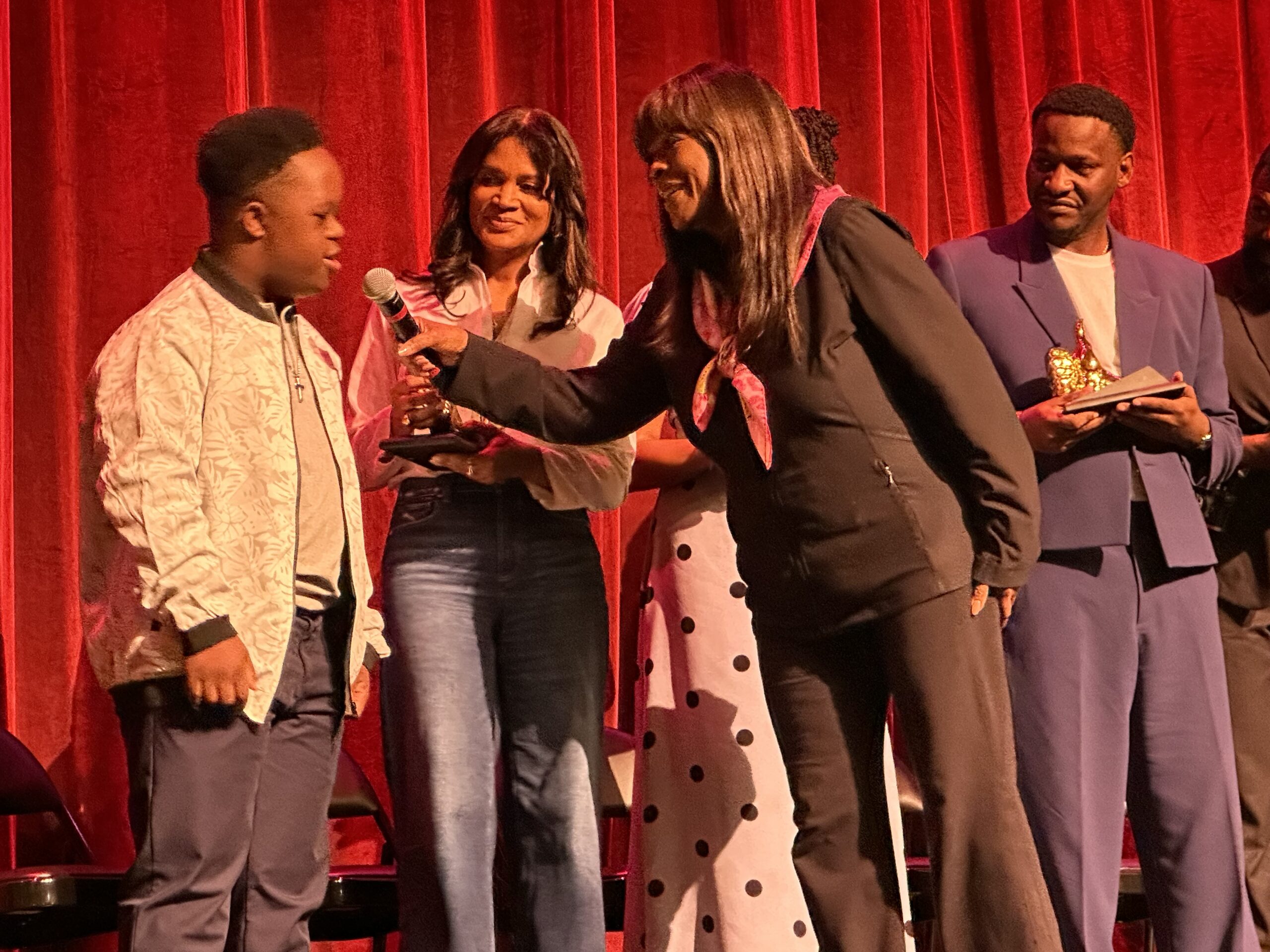

Saturday afternoon, Chaz introduced “Color Book” from writer-director David Fortune, which follows a day in the life of an Atlanta father (William Catlett) and his son with Down syndrome (Jeremiah Daniels) as they undergo an odyssey trying to get to a Braves game.

Fortune and both of his stars were joined by “Color Book” producer Kaya Klingman and Daniels’ parents, Joy and Terence. Fortune proudly shared that his young star is the first actor with Down syndrome to be nominated for an Image Award.

Fortune said the idea for the film came from his time at Loyola Marymount’s film school, to take a still photo and come up with a story behind it. He couldn’t shake the idea of telling a simple story about a Black man and his son, and setting it in his native Atlanta. From there, he made a short film called “Us,” which had many of the same elements as “Color Book.”

“I hope black men see this so that fatherhood can be celebrated,” said moderator Eric Pierson, a professor of communication studies at the University of San Diego.

Producer Klingman said that she and Fortune flew to New York to pitch the film at an AT&T Untold Stories program, successfully securing a $1 million grant. They had a year to deliver the film, even though the twin actors and writers’ strikes happened at the same time. They used Atlanta-based actors and crew as much as possible and filmed in black and white, which Fortune said allows the audience to focus more on the intimate father/son relationship. Personnel from MARTA, Atlanta’s rail system, were on hand to help film on moving trains.

Catlett, who portrayed the father Lucky, said that while another actor was scheduled to play Mason, the son, Catlett’s chemistry with young Jeremiah was undeniable.

“Immediately I knew that’s my son,” he said, adding that he will continue to be a presence in Jeremiah’s life.

“I’m a movie star and you’re not,” Jeremiah joked to director Fortune, which draw laughs from the crowd. Now 13, the young man said he hopes to continue acting.

Also on the panel was Annie Bruno, a licensed clinical social worker who works with disabled individuals. She said it was important someone with the “lived experienced” necessary to the character played Mason. Chaz echoed those sentiments, saying that there are so few films about African American men and their sons—even fewer about one with Down syndrome.

“Color Book” doesn’t yet have distribution, which Fortune said remains his primary focus so that “people can come together in one space and have a shared experience,” including the community he wrote it for.

Jeremiah’s mother Joy said that she gets emotional each time she beholds her son’s acting in “Color Book.”

“When he was born, we were told everything he wouldn’t do,” she said. “My husband and I, through our faith and through our village, treated Jeremiah the way we treated the rest of our children. It’s never been a question of whether he can do it, but when he can do it.”

“You raised me so well!” enthused Jeremiah next to his parents.