REVIEW – Carlos

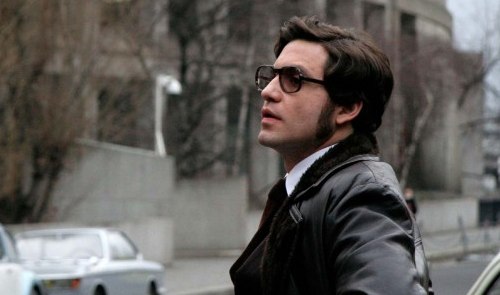

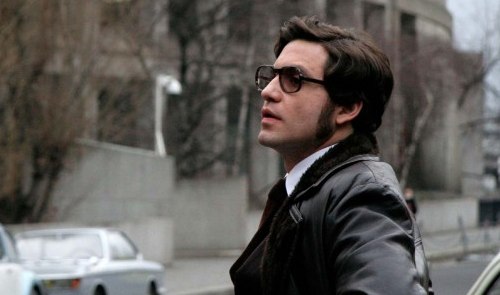

For this major undertaking director French director Olivier Assayas (“Summer hours”) spent two years researching his subject with the help of reporter Stephen Smith; final cost of the project? A mere nineteen million. “Carlos,” which in its original iteration lasted five hours and thirty-three minutes (the Cannes screening lasted that long, a major commitment for the journalist in attendance) is slow and deliberate at first and then things pick up halfway through. Does Edgar Ramirez, who shares a last name with his real-life counterpart, manage to carry the whole movie on his young shoulders? The answer is a resounding “yes.” What he may lack in on-screen experience (this is his first major role) he makes up for in charisma. Is “Carlos” the definitive gangster movie? Is it even a gangster movie?

A spate of films have recently treated the terrorist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, from “Baader Meinhof Komplex,” “Terror’s Advocate,” “Munich,” Marco Bellochio’s “Good Morning, Night” and now “Carlos,” about the famous terrorist Carlos the Jackal. My one and only real worry going in to see this was that Assayas would glorify the terrorist’s life. Fortunately this does not happen; also there’s no unnecessary rewinding of the tape, a life in homevideos: here’s young Illich (Carlos’s birth name, after Lenin) playing with a sock puppet at age 4 in Venezuela, etc. Assayas takes us directly into Carlos the Jackal’s first stages of a twenty-year long career as terrorist and so-called revolutionary (nihilist is more accurate, and what quality of life can a nihilist provide?).

Real-life Carlos, a Venezuelan citizen and a convert to Islam, has said: “From now on terrorism is going to be more or less a daily part of the landscape of your rotting democracies.” Whatever shadows lingered in my mind about his life before seeing “Carlos” still exist tonight. To me, people like Carlos are first and foremost products of the era they were born in, with the particularity that people like Carlos had a utopic bent to boot and a family background that would naturally orient him towards political activism. And yet, none of this begins to explain why Carlos became Carlos.

I thought “Der Baader Meinhof Komplex,” which is told along a punchier narrative, better conveyed the tension and violence that existed among the terrorist cells behind some of the deadliest attacks to occur in the 70s and 80s in Europe. Today’s “Carlos” by Olivier Assayas demonstrates, among others, the vitality but also the lack of discipline and organization in Carlos’ terror cell. The screwups pile up quickly but Edgar Ramirez’s Carlos never loses his resolve—this go-for-broke commitment to armed militancy is as impressive as it is weird. And while he appears to be a peace and human-loving individual at first, the psychopath that is Carlos the Jackal comes into clearer focus as the film progresses. Since the real Carlos is behind bars, French radio RTL interviewed him shortly before its premiere at Cannes last May and the Jackal was upset. He said, “the theme of this program is Carlos. It’s a biographical issue. They [the filmmaker / producers] did not even contact my lawyers, my family. They didn’t seek information from us. It’s regrettable.”